#fatma should have been executed

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Non Hurrem/Suleyman Scenes I Wish Had Been In The Series

**After Suleyman Returns To Find Hurrem Has Been Burned**

Suleyman questions everyone surviving Hurrem to find out how she's been doing scenes the attack. He's told she rarely leaves her chambers, she has the main entrance to her chambers bard every night and sleeps with a knife. Suleyman then calls an architect to design and build a new set of chambers contacted to his.

A few days later word begins to spread through the harem about the new chambers Suleyman has ordered. Hafsa and Mahidevran assume that the new chambers are for Mustafa.

**Sometime After Suleyman Returns To Find Hurrem Has Been Burned**

Suleyman has been back in Tapioca for a few weeks when Hurrem starts acting angry and jumpy. When he ask she says it's just nerves, so he questions Sumbal and Daya and is informed that Fatma the concubine responsible for burning Hurrem was brought back to the palace. Suleyman is furious and orders that Fatma be taken to the dungeons while he goes to comfort his mother.

**Immediately After Learning About Fatma**

Suleyman storms into the Valid Sultan's Cambers looking furious. Hafsa asks what's troubling him. Suleyman angrily confronts his mother about Fatma not only being brought back into the harem, but the fact that it's obvious that she wasn't truly punished. Hafsa try's to defend her actions to Suleyman despite the fact that he's obviously not buying it. At one point she says something that causes Suleyman to almost hit her, he stops himself before he even lifts his hand. He ends the conversation by telling her he will handle Fatma's punishment. He also tells her she needs to dismiss Gulsah because he will be appointing the new harem overseer.

**The Day After Suleyman's Confrontation With His Mother**

Suleyman has his mother and Mahidevran come to the viewing room used to over look events in the courtyard. There wondering why Suleyman has called them there, when he walks out. Their shocked to see him followed by Fatma who is being dragged by guards and an executioner. After Fatma is executed Suleyman looks up at the screen his mother and Mahidevran are standing behind before walking back into the palace.

**A Few Days After Fatma's Execution**

Word about Fatma's execution has spread through the harem. The concubines are gossiping and speculating about what this means for Valid Sultan's possession and the future of the harem. Sumbal inters to announce that Suleyman's has summoned Afife Hutan to take over as overseer of the harem, instead of Gulsah who Hafsa's chose.

**Early Season Three**

After her luncheon for the wives of Pasha and other high ranking men in the empire Hurrem holds a second uncheon for the wives and daughters of the foreign ambassadors. This event is held in the main area of the harem. Hurrem is using the mystery and speculation other countries have about the harem to guaranty the attendance of the women she's invited.

_I'm specifically basing this off of the scene in MC:K when Farya enters the harem for the first time._

**Early Season One Not Long Before Suleyman Returns From Campaign**

Hurrem is setting in her private chambers with Maria embroidering a blanket for the baby. Maria tells Hurrem that she's been worried that she'll be replaced as her concubine because she's not Muslim so she's going to talk to Sumbal about converting. Hurrem tells her she doesn't have to do that, she'll talk to Suleyman to make sure that doesn't happen. Maria responses that she rather do everything possible to make sure there not separated. Hurrem leans over and hugs Maria thanking her.

**The Night Hurrem Gives Birth To Mehmed**

Ibrahim has ordered Gulnihal to be sent to Halvet. As Sumbal is taking her to be prepared she's protesting that she can't do this to Hurrem. Sumbal tells her to keep quiet and when she's in left alone with Suleyman to introduce herself by her old name and nothing will happen. She nods her head and says okay, then keeps quiet while she's prepared.

When she's left alone with Suleyman she introduces herself as Maria, then drops to her knees and say she can't be here because it would break Hurrem's heart. Suleyman realizing that this is Hurrem's Maria who he'd given Sumbal instructions not to send to halvet he's furious. She gives an explanation that Ibrahim picked her and that there was probably confusion because she'd just converted and has been given her new name.

After Suleyman has calmed down they began talking with Maria telling Suleyman stories about Hurrem and her life before the harem with Maria telling him she was revealed to see Hurrem finally starting to live again. A few hours into their conversation Sumbal arrives to inform Suleyman that Hurrem is in labor.

**Season One Early Into Hurrem's First Pregnancy**

Hafsa tells Daya she has decided to marry Hurrem off while Suleyman is on campaign. Daya asks if she'd like her to take Hurrem to be examined immediately to confirm she's not pregnant or wait until a groom has been selected. Hafsa tells her to have the exam done immediately because she doesn't need the stress of having to back out of and engagement if she is pregnant.

_Hafsa trying to marry Hurrem off without finding out if she's pregnant or not was one of her stupidest designs in the inter series._

@redxluna @desmoonl @shivrcys @faintingheroine @minetteskvareninova

#magnificent century#muhteşem yüzyıl#hurrem sultan#sultan suleyman#mahidevran#hafsa sultan#fatma should have been executed#suleyam loves and protects hurrem

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

I believe that Suleiman did not have a daughter named Raziye. But why?

During my trip to Istanbul, I visited Sultan Selim Mosque.

There were five tombs in the mausoleum of the p

Șehzadeler, where Suleiman's young children are buried.

In addition to the tombs of Mahmud Murad and Abdullah, there were the tombs of two other children.

We know that Suleiman's two sons, Mahmud and Murad, died in 1521. The following year, Suleiman's eldest daughter died.

In 1522, Yahya Effendi was still very young. It is not clear whether he was even then a priest or not.

On the other hand, at this time, Yahya had not built a tomb for himself to bury the Sultan's daughter in. More strangely, all three young sons of the Sultan were buried in the royal tomb.

Why should the Sultan bury his young daughter in the tomb of a cleric? A tomb that had not yet been built.

I think the young girl is buried next to her brothers in Sultan Selim Khan Mosque.

On the other hand, there are five graves instead of three in the mausoleum of the princes. I don't know who the fifth tomb belongs to, maybe it is one of Suleiman's children, but surely one of those tombs belongs to the Sultan's little daughter.

But as for Raziye Sultan, I think she was the daughter of Şehzade Mustafa.

Husamodin Husayn, the 19th century historian, mentions in the history of Amasya that Şehzade Mustafa had four children: Suleiman, Mehmed, Fatma and Raziye. In his book, he mentions that the girl who married Ahmad Pasha was Fatma Sultan. If I am not mistaken, his source for this statement is the writing of one of the Venetian ambassadors.

On the other hand, we know that Yahya Effendi supported Mustafa's family after his execution. It is not strange that one of his daughters is buried in this man's grave.

From time to time this topic comes up, Polybius would say that’s because history is cyclical lol.

I know the tombs do not correspond to Süleyman I’s known children but that Raziye was the sultan’s daughter was proved by Şehsuvaroğlu, who found that the sarcophagus in Yahya Efendi’s mausoleum had an inscription that said: “Kanuni Süleyman’s daughter and Yahya Efendi’s spiritual daughter the carefree Raziye Sultan”

Yahya Efendi is mentioned as her spiritual father because he and the sultan were milk brothers.

I think Raziye may have been re-buried there, though we don’t know why. It’s not even certain that Süleyman himself re-buried her, maybe something had happened to where she was buried and therefore her sarcophagus was moved.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thanks for the answer! I hope you don’t mind if I reblog instead of sending a new ask entirely.

It’s interesting you pointed out about the report of 1627 from Giorgio Giustiniani that he claimed both Hasan and Mustafa were Murad IV’s brothers-in-law. When I first read it, I focused a lot on the story told by Giustiniani that Hasan had been "chiecaià" of the Old Kizlar Aga (Haci Mustafa?) and who told Kosem about Osman trying to kill Mehmed and Kosem being able to stop it thanks to him... Which would mean Osman tried to kill Mehmed before January 1621, but was unsuccessful in it due to Kosem (did Baki Tezcan never noticed this? I think it would`ve been a nice addition to his article of Kosem being Mehmed's mother)...

But since I was too focused on that part, I let it slip by that Hasan was called a brother-in-law already, and when I read about Mustafa, I simply connected him to Kara Mustafa Pasha, who is ascribed as Fatma Sultan's husband. Anyway, what bugs me here is what should be Kara Mustafa Pasha's real death date if he's the Mustafa who had been executed for keeping corrupt money mentioned by Giustiniani, in around July 1627. Oztuna and Sakaoglu both claim Kara Mustafa was executed in 1628, and Joseph von Hammer mentions a report that claims the King's brother-in-law Mustafa was executed dated December 1627... Anyway, I believe the Mustafa is Kara Mustafa Pasha, but then why did Giustiniani not mention that Hasan had been given Mustafa's widow, assuming his death had been recent to the point it was even mentioned in the report? And if it's him, then Peirce is completely wrong by saying Fatma was married to Kara Mustafa after divorcing Hasan in 1628.

And I don't think Giustiniani was talking about a third Kenan Pasha, it's Koca Sofu Kenan Pasha, but this confirms he received Burnaz Atike in marriage in 1627 or before. Or maybe it was still a betrothal?

Indeed my question had been about the names and whether Ibrahim's Atike existed separately from Gevherhan, who appears with her own name as the wife of Sari Kenan and Ismail by Ragusans and Rycaut, marriages that are ascribed to Atike.

As for Sakaoglu, I do not understand why he corrected Gurcu Mehmed to the other Mehmed. As you say, the other Mehmed was indeed never governor of Buda, while Gurcu Mehmed was and his age fits the description more because he had surely been a very old man in 1660s, as some say he was the slave of Grand Vizier Koca Sinan Pasha who died in 1596, so he couldn't have been younger than what, 75 at his death in 1665 (and maybe he just aged very badly that people thought he really was 90)? I suppose it might be because two sisters getting married to two Mehmeds in one single decade could be hard to believe, especially if the historian could not find an Ottoman chronicler that talked about the damadhood of Gurcu Mehmed. And then there’s the fact that besides Haseki Mehmed (d. 1661), they also believe it could've been Çavuşzade Mehmed (d. 1681) instead, which makes everything even more complicated and impossible to solve without more sources on the matter.

I do wonder if there's a big possibility only Beyhan and Gevherhan were alive in 1672, as by that date Mehmed is recorded to have only brought these sisters to Babadag. What would be the reason to exclude other sisters if there were any others? So many questions...

Again, thank you so much for the answer!

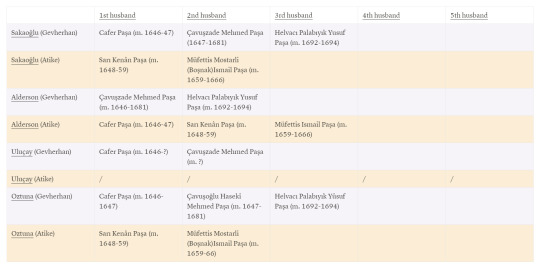

Hi! Previously in Ottomanladies you answered an ask about marriages of Burnaz Atike, Gevherhan and little Atike. So, some historians confused Burnaz Atike with one of Ibrahim's daughters when they claim she married Musahib Cafer Pasha (d.1647) in 1630, as according to Giorgio Giustinian in 1627, Koca Kenan (d. 1652) was already married to Murad IV's sister (Pedani, p.596). And some historians say Gevherhan was the one who married Cafer in November 1646, like Sakaoglu.

And according to Joseph von Hammer, the youngest daughter of Ibrahim betrothed to Cafer was married to the other Kenan, Sari Kenan (d. 1659). But some historians separate the wives of these pashas as Gevherhan marrying Cafer and her sister Atike marrying Sari Kenan, with Atike going on to marry Ismail Pasha.

However, in "Dubrovacka akta i povelje", a report of 1650s refers to "Ghiusciahato sultana moglie di Chieman passa", so it seems to me she married Sari Kenan after Cafer died. And the "Mémoires du Sieur de la Croix" in 1670s, pages 368, 369, 370 and 371 says: "Les soeurs du Grand Seigneur (...) la premiere fut mariée à trois ans, & eftoit à dix avec fon second mary Affaki Mehemet Pasha, Gouverneur dAlep, il fuit étranglé fous pretexte de fauffe monnoye, & elle fe maria pour la troisiéme fois avec Ibrahim Pacha Tefterdar, du depuis Pacha du Kaire, dAlep, & enfin Capitan Pacha, aprés la mort duquel Jemblat Oglou Gouverneur du Kaire la épousée en quatriéme nopces. La seconde mariée auffi jeune que sa soeur, a eu cinq maris, dont le dernier la prit vierge, à cause dun défaut de nature (...) Je ne fcay pas le nom des deux premiers, le troisiéme fut Sinan Pacha, lequel estant Capitan Pacha, perdit la Bataille des Dardanelles (...) Le quetriéme eftoit Ismael Pacha, ce grand Seigneur l ayant choifi pour und es Lieutenans generaux de l armée dHongrie (...) Le cinquiéme sappelle Kassum Pacha, il est Chirurgien de profession"

The quote says Mehmed IV had 2 sisters in 1670s. The 1st married Haseki Cavuszade Mehmed Pasha, then Defterdar Ibrahim Pasha and then a Canpulatoglu (son of Kosems Fatma?). The other, younger than the first, was married to "Sinan" who was Kaptaniderya, so it should be Sari Kenan. After him she married Ismail Pasha and then Cerrah Kasim Pasha, and also had 2 husbands before the first.

(All in all, I believe the first sister who married Haseki Cavuszade could be Beyhan instead, as in 1653, according to "Dubrovacka akta i povelje" she is called "Behar sultana, moglie di passa di Cairo", and in 1563 this was Haseki Cavuszade Mehmed; but interestingly historians believe he was Gevherhans second husband instead...)

In "Per favore della Soltana", several lists give us marriages of Gevherhan. In 1648, she is called widow of Cafer, in 1662 she is wife of Ismail Pasha, and in 1670 she is called wife of Casciu Pascia who is probably Cerrah Kasim Pasha. And in 1676 and 1680, she is called wife of a Canpolatoglu and not another Sultana as Croix claimed.

Paul Rycaut in "The Present State of the Ottoman Empire" also says Gevherhan married Ismail Pasha (and then remarried to Gurcu Mehmed Pasha): "At this tenderness of age, Sultan Ibrahim, father of the present Grand Signior, married three of his daughters, one of which was called Gheaher Han Sultan, hath had already five husbands, and yet as is reported by the world, remains a virgin; the last husband deceased was Ishmael Pasha, who was slain in the passage of the River Raab; and is now again married to Guirgi Mehemet Pasha of Buda".

So it seems to me that Gevherhan married the following: Musahib Cafer in 1646, Sari Kenan in 1647, Ismail Pasha after him, then Gurcu Mehmed, then Cerrah Kasim Pasha, and then maybe a Canpulatoglu (unless that was the other sister like Croix claimed, maybe Beyhan?), before finally marrying Palabiyik Yusuf later in life.

But after all this, I want to ask whether its possible that this sister of Mehmed IV called Atike existed at all? Because it seems quite certain that Gevherhan married Kenan Pasha and Ismail Pasha, not one named Atike, and historians did make a confusion with Burnaz Atikes marriages. And if little Atike didnt exist, was Gevherhan the full-sister of Mehmed IV instead? I know Gevherhan is believed to be born in 1642, and with Mehmed and Fatma it gets too much for Turhan, but Hammer describes her as the youngest daughter in 1647, and if the sister who married Haseki Mehmed was Beyhan, and she was reportedly married for the first time to another at the age of 3 as Croix claims, and the sister who married Sari Kenan and the others was younger than her, then Beyhan could still be born in 1645 as she married Hezarpare in 1648, and Gevherhan was born after her...

Hi! Please be patient with me because these asks take time to unwrap and I’m only doing this in my free time.

I think you’re talking about this ask. About the confusion, it’s something that Uluçay too believes:

Alderson confused the daughters of Ahmed I, Murad IV and Sultan Ibrahim, so he made mistakes.

Alderson confused the daughters of Ibrahim with the daughters of Ahmed I and Mehmed IV, and therefore made some mistakes.

and he’s right because the rapid successions plus the practice of marrying princesses as children created so much confusion.

(it’s so funny that he says that twice lmao)

Okay, so your theory is that Atike Sultan binti Ibrahim doesn’t exist and that some historians seem to have mistaken Burnaz Atike with a daughter of Ibrahim? I hope I understood well.

Everything under the read more (it's very... heavy, sorry lol)

I read Giustiniani’s relazione and the math is not really mathing because he says Murad IV put his four brothers-in-law at the highest posts of government but then mentions five brothers-in-law:

Çatalcalı Haşan Pasha: he’s Fatma’s husband

Hafiz Ahmed Pasha: he’s Ayşe’s husband

Bayram Pasha: he’s Hanzade’s husband

(Recep Pasha: he’s Gevherhan’s husband) > Giustiniani only mentions her as Osman II's elder sister

“Chinan” who, you believe, was Koca Sofu Kenan Pasha

“Mustaffà” ?? who is he??

Sicill-i Osmani says that Kenan Pasha married Burnaz Atike in 1633-34, but Giustinian’s last dispatch from Istanbul was dated 4 July 1627 so… did he foresee the future? Were there more Kenan Pashas?

(Also, who is that Mustafa??)

Now, onto Ibrahim's daughters.

So, I made this table to semplify things because I was going insane with all the information.

I think there is some confusion between Haseki Mehmed Pasha, who was strangled in Aleppo in June 1661 (like de la Croix says), and Çavuşzade/Çavuşoğlu Mehmed Paşa, who lived until 1681. Sicill-i Osmani doesn’t call the latter “Haseki” but he’s identified as Gevherhan Sultan’s husband. Now, the princess who married Haseki Mehmed Pasha could have remarried after 1661, but the one who married Çavuşzade/Çavuşoğlu Mehmed had to wait until 1681.

Beyhan is admittedly a mistery because she was married for less then a year to Hezâr-pâre Ahmed Pasha when she was little but afterwards didn’t have a husband for 11 years? It seems strange. If the Ragusian diplomats called her “wife of the pasha of Cairo” and if Haseki Mehmed Pasha was beylerbey of Egypt in 1653 (as Oztuna confirms in Devletler ve Hanedanlar), then Haseki Mehmed Pasha was married to Beyhan binti Ibrahim. Unfortunately my only Ragusian sources come from the essay Per Favore Della Soltana, and in it there’s a gap between a letter dated 1648 and one dated 1662.

About the Canpulatoğlu Pasha, I would like to add that Canbulad-zâde Mustafa Paşa had two sons with Fatma: Sultânzâde Hüseyn Paşa, who was governor of Budin and of Egypt, and Sultânzâde Süleymân Bey. Both lived to adulthood. Moreover, he had a daughter from his previous marriage: Ayşe Hâtûn. Maybe he had other sons too. It is interesting, though, that de la Croix says Canpulatoğlu is Governor of Egypt, because Sultânzâde Hüseyn Paşa was indeed governor of Egypt at some point.

About Atike binti Ibrahim:

(Uluçay doesn't believe she existed)

As we can see, Oztuna and Sakaoğlu use the same source. Oztuna, though, says that Atike binti Ibrahim was buried in Ibrahim’s mausoleum, while Sakaoğlu says that her burial place is unknown. Curiously, Atike binti Ahmed I is buried in Ibrahim’s mausoleum too.

Since Alderson gave his sources, I went to check. This is a passage from Histoire de l’Empire Ottoman, volume 12, pp. 49-50:

L'ainée, Aïsché, fiancée dès l'age de trois ans à Ipschir-Pascha, épousa à dix Mohammed-Pascha, gouverneur de Haleb; ce dernier ayant été décapité comme faux monnoyeur, elle devint la femme du defterdar Ibrahim, gouverneur du Kaire, puis de Haleb, et alors kapitan-pascha; à sa mort, elle fut mariée à Djanbouladzadé, ancien gouverneur d’Ofen, qui depuis remplit les mêmes fonctions au Kaire. La seconde, nommée Aatika, épousa d'abord le vizir Kenaan-Pascha, puis le vizir Yousouf-Pascha, et en troisième lieu le kapitan Sinan-Pascha, qui avait perdu la bataille des Dardanelles contre les Vénitiens; elle eut pour quatrième époux Ismail-Pascha, grand-inquisiteur en Asie, qui fut tué à la bataille de Saint-Gotthardt; enfin elle contracta une cinquième union avec KasimPascha, l'un des pages de la chambre intérieure, et chirurgien de profession, qui, lors de la circoncision du sultan Mohammed , sut arrêter, au moyen d'une poudre astringente, une hémorrhagie qui avait fait tomber le prince-en défaillance, service que ce dernier récompensa plus tard en donnant à Kasim le gouvernement de Temeswar. […] le Sultan, en reconnaissance du sang qu'il lui avait conservé, refusa de répandre le sien, et, pour le sauver, lui donna la main de sa sœur, qu’un vice de conformation avait empêchée d'appartenir à ses premiers maris, et qui, après dix-neuf ans de mariage, entra vierge dans le harem de Kasim. Celui-ci la délivra de son infirmité au moyen d'ine opération qu’il pratiqua pendant le sommeil d'Aatika, assoupie par un narcotique. Ce fut ainsi qu'il acquit des titres puissans aux bonnes grâces de la princesse, comme précédemment il avait mérité la faveur particulière de Mohammed IV.

Doesn’t it kind of sound like de la Croix (below)? I think Hammer’s source is him.

"La premiere fut mariée à trois ans, & estoit à dix avec son second mary Assaki Mehemet Pasha, Gouverneur d’Alep, il fut étranglé sous pretexte de fausse monnoye, & elle se maria pour la troisiéme fois avec Ibrahim Pacha Tefterdar, du depuis Pacha du Kaire, d’Alep, & enfin Capitan Pacha, aprés la mort duquel Jemblat Oglou Gouverneur du Kaire l’a épousée en quatriéme nopces. La seconde mariée aussi jeune que sa soeur, a eu cinq maris, dont le dernier la prit vierge, à cause d’un défaut de nature (...) Je ne sçay pas le nom des deux premiers, le troisiéme fut Sinan Pacha, lequel estant Capitan Pacha, perdit la Bataille des Dardanelles (...) Le quetriéme estoit Ismael Pacha, ce grand Seigneur l’ayant choisi pour un des Lieutenans generaux de l’armée d’Hongrie (...) Le cinquiéme s’appelle Kassum Pacha, il est Chirurgien de profession”

Now, I think Hammer starts with a mistake because Ibsir Mustafa Pasha was one of Ayşe binti Ahmed I’s husbands. Also, it’s impossible to say where he found that Mehmed IV’s eldest sister was named Ayşe. After these mistakes, though, he repeats what de la Croix said: Haseki Mehmed Pasha, Defterdar Ibrahim Pasha, Canbuladzâde Pasha. The second sister is named Atike (so he says) and stayed a virgin until her last husband, Cerrah Kasim Pasha, operated on her to solve some kind of physical problem she had. This story is similar to the one reported by Rycaut, but he named her Gevherhan instead:

At this tenderness of Age, Sultan Ibrahim, Father of the present Grand Signior, married three of his Daughters; one of which called Gheaher Han Sultan, hath had already five Husbands, and yet, as is reported by the World, remains a Virgin; the last Husband deceased was Ishmael Pasha, who was slain in the passage of the River Raab; and is now again married to Gurgi Mahomet Pasha of Buda, a Man of 90 Years of Age, but rich and able to maintain the greatness of her Court, though not to comply with the youthfulness of her Bed, to which he is a stranger like the rest of her preceding Husbands. — p. 40.

It’s possible that Rycaut had already left the Ottoman Empire when this princess married Cerrah Kasim Pasha. He’s the only one talking about Gurci Mehmed Pasha, though… Interestingly, Sakaoğlu corrects Rycaut’s Gürcü into “(Çavuşzade, Haseki)” but, admittedly, his quote is quite different from Rycaut’s original. In Sakaoğlu’s it is said that the pasha is 30, while Rycaut says he’s 90. Moreover, as far as I know, Çavuşzade Mehmed Pasha was never governor of Buda.

In conclusion, I’m more confused than before lol

As for Mehmed IV’s full sister, I really have no opinion on this. Usually, it’s Beyhan who is given as Turhan Hatice’s daughter but with no hard evidence.

You (and other people) can send me asks on ottomanladies now, I have re-opened my ask box. As I have already said, please be patient with me because I don't have much free time and these things need to be analyzed properly :D

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Murad IV / IV. Murad portréja

Birth and childhood

Murad was born in July 1612 as the second son and fifth child of Ahmed I and his favorite concubine, Mahpeyker Kösem. In addition to Ahmed's two sons from Kösem, Ahmed had another son, Prince Osman, the eldest child. Murad belonged to a generation of princes who, for the first time in history, did not have to fear the law of fratricide. According to a tradition enshrined in law by Mehmed II, sultans had to execute all of their brothers in order to maintain order. However, Sultan Ahmed did not do this when he left his brother, Mustafa, alive after his accession to the throne in 1603. Thus the sons of Ahmed were already born into a new world. It is a fact, however, that Ahmed was not sure of his decision for a long time, so he repeatedly attempted to execute Mustafa, but in the end, his conscience and Kösem Sultan convinced him, so Mustafa was saved.

Murad lived his early childhood in relative calmness, as his father was a popular sultan, his mother held the rank of Haseki Sultan, and she was a very influential and popular woman. However, all this changed in 1617. Sultan Ahmed died and a kind of inheritance chaos broke out in the empire. The people had enough of the fratricide but Ahmed had not left a legal decree about who should follow him on the throne: his younger brother, Mustafa, or his eldest son, Osman. Eventually, with the accession of Mustafa to the throne, the inheritance officially changed, the throne no longer passed from father to son but was taken over by the oldest male of the dynasty. So Murad and his siblings could survive, but they lived in solitary confinement in Topkapi Palace, while their mother Kösem Sultan along with her daughters moved to the Old Palace.

The following years were quite chaotic, Mustafa was soon dethroned because of his mental illness, and Murad’s half-brother, Osman, ascended the throne. Osman was a very unpopular, bad ruler who, although tried to maintain a fair relationship with Kösem Sultan in his early reign, he later in January 1621 executed Kösem's son so Murad's brother, Prince Mehmed. Murad and his younger brothers certainly lived in awe away from their mothers, their sisters, locked up, exposed to a tyrant ruler, and it cannot be ruled out that they witnessed the execution. Eventually, Osman's brutal murder brought relief to them. But it also gave Murad a lifelong lesson that not even a sultan can be safe.

Accession to the throne

The brutal execution of Osman was attributed to Halime Sultan and her son, Mustafa I, so that Sultan Mustafa was eventually dethroned again and his mother exiled to the Old Palace. Murad, just 11 years old, was the next in the line of inheritance. Given his age, the divan and ulema appointed his mother Kösem Sultan as a regent, until Murad himself became mature enough to rule. Although Murad could relief as he became the sultan, it was certainly not easy for him to start a new life after such a difficult childhood. It is also important to note that Murad was able to spend some time with his mother last time in 1617 at the age of five. He lived separated from his mother for six years between 1617 and 1623, this presumably caused serious difficulty for the two of them to re-establish a mother-son relationship.

Murad was a difficult child to handle. Several letters of Kösem Sultan have survived in which she complains to the Grand Vizier about how much Murad does not listen to her, and sometimes he even refuses to meet her for days. In addition to the long isolation, their similar personalities did not help to form a nice relationship much either. They were both leading individuals, with a very strong will, so they had a hard time getting along with each other. They argued many times, after which Kösem Sultan was the one who wanted to reconcile with Murad. After one of their big quarrels, for example, she gifted a horse to Murad, and at other times she organized a huge ceremony for him. In addition, Kösem has regularly expressed concern about Murad’s health, suggesting that perhaps Murad was already struggling with health problems at the time.

From the time of Ahmed's death, the empire gradually fell into anarchy. They lost several important areas and tried in vain to recapture them. Furthermore, Abaza Mehmed Pasha, who revolted after the execution of Osman II, refused to recognize Murad as his ruler and continued his rebellion. Nor did this rebellion was suppressed by the pashas sent against him. To exacerbate the situation, in 1625 a plague broke out in the capital, killing thousands of people. For the first time in the same year, Murad rebelled against his mother’s will. Kösem made a treaty with the Spaniards at the time, but Murad did not like that, so in the end, Kösem gave up.

Then in 1628, Murad became seriously ill, lying in bed for weeks. His exact illness was not revealed, some said his epilepsy started at this time, others said he had digestive problems. But good things also happened that year, Abaza Mehmed Pasha’s rebellion finished and they captured him. In the same year, Murad gave another signal that he soon wanted to take over the reign and openly confronted his mother when he dissolved his sister Fatma’s marriage to Admiral Çatalcalı Haşan Pasha, whom his mother had given special attention to. In addition, Murad was increasingly disturbed by the fact that his mother let corruption go on. Kösem Sultan herself also gave special attention to pashas she liked and this provoked resentment from many, especially her son, Murad. For example, Kösem gave a very important Janissary position to Hafiz Ahmed Pasha, the new husband of Murad's sister, Fatma. However, this was too much for the Sipahis and the Janissaries. In the end, it was the event that marked the beginning of Murad’s absolute monarchy.

The absolute monarch

In 1632, after the appointment of Hafiz Ahmed Pasha, a Sipahis and Janissary rebellion broke out, during which the rebels executed several loyal men of Sultan Murad, including his close friend Musa Çelebi. To make matters worse, the soldiers publicly demanded that Murad show them his younger brothers. By doing so, they wanted to signal to him that if they wanted to, they could replace him with one of his brothers; on the other hand, such unfounded rumors circulated that Murad and Kösem got rid of the princes. Murad was forced to show his younger brothers. Murad never forgot this and never forgave either the rebels or his brothers. In fact, Murad was immeasurably humiliated at that time, he lost his allies and close friends. No ruler could leave that unrevenged. However, Murad was thoughtful and intelligent enough not to take revenge immediately but only execute the chief rebels when his power was consolidated a few months later.

Either way, after the rebellion in May 1632, Murad took control and resigned his mother from the regent position. Kösem Sultan did not object, she stood aside, but she would have tried to help her son, show him the way. Murad did not appreciate this and did not listen to his mother's advice. Murad was compulsively trying to keep his mother away from politics, and it is clear from his actions that he was disturbed by his mother’s great influence. That is why, as soon as he took power under his own control, Murad sought to replace his mother's men, such as his own brother-in-law, Hafiz Ahmed Pasha, who had already been mentioned, so that he could begin his monopoly by withdrawing himself from his mother's influence.

Although Kösem and Murad's relationship was undoubtedly stigmatized by the 1632 uprising, it would be a mistake to think that Murad completely excluded his mother from his life. He always respected her as the leader of the harem and as his mother, and according to a report from 1632, he even asked for his mother's opinion on his private life. Namely, Knolles reported at this time that after the birth of Murad's seventh daughter, he wanted to marry (or rather gave the Haseki rank) to the child's mother to express his love for the woman, but before he did so, he asked for Kösem's opinion. It is an interesting question of who this woman was, for we know of the only privileged consort of Murad’s early reign was Haseki Ayşe Sultan, but we do not know exactly who her children were and when they were born.

Also, when Murad left the capital for a shorter period, he always left his mother as a supervisor, and Kösem Sultan always reported everything accurately to her son. When Kösem noticed a problem, she immediately signaled it to Murad with the most detailed description. A concrete example of the former occurred in 1634, when, in Murad's absence, Kösem learnt that a mufti had not accepted one of Murad's decisions and wanted to review it. She immediately sent a message to her son, “My heroic lion, come immediately. There are rumours of intentions towards the throne and people are starting to gather”. Murad didn't need anything more, he returned immediately and executed the muft without any investigation. It was the first such event in the history of the empire, they had never executed a mufti before. On another occasion, Murad asked Kösem Sultan to do a diplomatic talk with the Crimean Khan.

The tyrant

Murad's personality is very divisive. Many consider him simply a tyrant, but he is more than that. Many times his cruel acts certainly stem from his difficult childhood and his fear of dethronement. Plenty of legends are known about his cruelty, like that he killed people for pleasure and often tortured them innocently, but also we can hear such things that the Sultan ran through the streets at night with a sword and killed anyone who came face to face with him. In this form, these are, of course, just lies and very strong exaggerations. But it is a fact true that he had many acts that did not make him particularly popular. Kösem Sultan tried to influence her son in every possible way and tried to cushion her son’s aggressive actions with her own charities.

Murad banned alcohol and tobacco and even closed all cafes because he thought the Janissaries and Sipahis gathered and allied against him there. And whoever broke the rules could face severe punishment, even the death penalty. To keep his orders, he often go to the streets in disguise and acted in person against those who violated the ordinance. But it is also a fact that if he experienced an injustice or a frustrating thing at these times, he also tried to do against it. He also changed a lot of basic laws, tightened penalties, and made the death penalty more common for even minor offenses. Legends commemorate a case in which he executed a vizier for beating his mother-in-law. At other times, an ambassador, Alvise Contarini, was imprisoned for a minor crime. Contarini's accounts became unreliable after this incident, as he often wrote lies and exaggerations about Murad because of his personal resentments. This was the case, for example, when Contarini reported that Murad was systematically threatening his mother, siblings, and concubines with a beating. However, all the other evidence reports statethe opposite, claiming he was very nice to his family, so behind that account, perhaps Contarini’s dislike have been the only reason.

While there was no doubt that Murad’s austerity was excessive, he managed to put the empire in order, chaos and anarchy seemed to actually be resolved. Murad sat on the throne after chaotic times when the sultans were less respected by the people than any time before. In the time of Suleiman I, the sultan was almost a deity, an inaccessible, superior creature. And a sultan had to maintain this appearance in order to rule an empire of this size. In the chaos that followed the death of Ahmed I, the people saw, on the example of Osman, that the Sultan was indeed a mortal, simple man, the divine image built over the centuries was destroyed. Murad tried to rebuild this. When this did not go in an easy way, he did so in the way of violence and rigor, but anyway he established order in his country.

Not surprising, that Murad considered Yavuz Selim I as his role model, who controlled with strictness, and who did not tolerate contradiction. Murad, following the theory of his teacher, believed that the decline of the empire began during Suleiman's reign, so it was clear that a former successful sultan had to be imitated by him. In addition, Murad had an undisguised goal of restoring the old succession-system. Although he owed his own life to the change of the succession-system, he still believed it posed too many dangers if a Sultan had rivals roughly the same age and same education as him. While many people clearly condemn this, we have to admit, there was truth in this. The brutal execution of Osman and the way as they used Mustafa as a puppet, are all good examples of how dangerous was the existence of brothers. Murad wanted his own son as his heir, which is why he executed his younger brothers over time, except for the mentally unstable Ibrahim. This, by the way, raises several questions, especially about the sons of Murad.

There are quite a lot of question-marks about Murad’s children. We know from Evliya Çelebi's accounts that Murad had many sons, but almost without exception they all died in infancy, for they were born in rather poor health. Unfortunately, for most of his children, we don’t know when they died. What is certain is that in 1634, according to an ambassadorial report, he had two infant sons in poor health. However, despite these, we must assume that when Murad executed his brothers (1635, 1638) there must have been at least one living son of his who was no longer an infant. His eldest son, Ahmed, was born in 1627 and many say he lived the longest, though no exact date is available for his death. There are also those who say that Murad did not have an older living son at these times, he simply wanted the end the dynasty, so he killed his brothers. The latter is supported by the fact that at the time of Ibrahim I's accession (1640) there was not a single son of Murad alive, so perhaps none of them were alive in Murad's last years. However, this does not mean that in 1635 and 1638 he did not have a son who was still alive. All we know from an ambassadorial account from 1637 is that at least 6 sons of Murad died before the age of one, and the health of the others was very fragile. But we don’t know what and how many children the author meant by the others.

Murad, the individual

We are forced to consider Murad as a tyrant in some ways, even with the utmost benevolence, as his decrees and his punishments, often unbalanced with the degree of sin, suggest so. At the same time, Evliya Çelebi's descriptions reveal much more about Murad's personality. Based on these, it seems that the cruel Murad was just a mask behind which the sultan hid his true nature. Murad believed that people and his soldiers will respect him only if they were afraid of him. We must understand that in such era it was logical. All his actions suggest that also, so maybe that’s why he played the cruel Murad role. Of course, this could not have been very far from his true personality, since otherwise, he would not have been able to carry out his cruelty that much.

But what do we know about Murad, the individual? According to others, he was an extremely intelligent, educated man with a very good sense of humor and was a talented poet. According to Evliya, "He was an emperor with a dervish’s nature, kind-hearted and devil-may-care." The latter analogy may have been particularly fitting to Murad because he had great respect and appreciation for the whirling dervishes. So much that he honored a dervish named Ömer with the address "my father." By the way, they often made music together with Ömer. Murad wrote the lyrics and the dervish added the melody. And we know for sure that, contrary to rumors, Murad was not crazy. He was characterized by a certain level of paranoia, but given what had happened to him in the past - he first-hand experienced his brother's death and then his half-brother's brutal murder - was not particularly surprising. However, among the people he loved and trusted, Murad blossomed and showed his true face. The real Murad was a young man in full force, with whom they could humorize even about the most personal things, with whom they could have fun and converse about serious things at the same time. However, Evliya did not doubt that Murad was a very stubborn and strong-minded man, especially towards his mother.

Evliya is also associated with a famous (or infamous) story that many consider the Sultan to be homosexual. The point of Evliya’s story is that they talked to the sultan about a beautiful person, Handan, who the sultan loves and who Evliya says is really charming also. According to the story, the sultan asked Handan to take a rose from his/her hair and give it to Evliya to cheer up the grumpy Evliya. There would be basically nothing special about the story if it all happened in a Western empire. However, knowing the customs of the Ottoman Empire, it becomes clear to us that Handan could not have been a woman, since a harem concubine could not be in the company of foreign men, especially not with uncovered hair. It also makes it difficult to accurately recognize Handan that the name 'Handan' is a unisex name and that there is no male or female gender in the Ottoman language so we cannot know if Evliya talks about a he or a she. Because of this, many people think that Handan was a eunuch or a young man. It is important to know that in the Ottoman Empire until the mid-1800s, homosexuality was accepted, not punishable. In most brothels (because they were also present in the empire) not only women but also men were available. In addition, since Sultan Mehmed II, pederasty has been accepted among sultans and pashas. Mehmed II (who was probably really gay or bisexual) inherited this ancient Greek tradition, which refers to the homosexual relationship between an adult man and a man much younger than him, after the conquare of Constantinople. Later, there were sultans who took advantage of this opportunity and there were those who did not. However, pederasty was primarily a status symbol rather than a relationship driven by sexual desire.

Many have also rumored that Kösem Sultan has sent men to Murad’s bed when he was young, but there is no indication that this is true. Either way, Murad’s sexual orientation will probably never be revealed and maybe it doesn’t even matter. There were two significant concubines in his life, Haseki Ayşe Sultan, who dominated his reign almost throughout, and who, in addition to Esmehan Kaya, must have been the mother of several other children; and there was another woman whose name could not be reconstructed and who came to Murad's life in the last years of his reign and who became a Haseki also. Ayşe, however, was certainly Murad's favorite throughout his reign, as he even took her with him to his Revan campaign. This thing occurred in the case of the early sultans quite often, but from the early modern period of the Empire, sultans did not let their wives and consorts accompany them to war as it was quite risky.

From the tyrant to the adored sultan

Like Murad’s predecessors, he was aware that the fastest way to gain popularity was a successful campaign. Murad was under particular pressure, for at the beginning of his reign they lost particularly important territories, so he had to somehow rectify this. Murad was truly a man of a warrior nature, and there are also legends about his physical performances. It is true that his health was not very good, but he had a very strong physique. He was a tall, robust man with black hair and eyes and pale skin. So Murad, in addition to being handsome with his physical strength, was also able to impress his subjects on a regular basis. Legends revolve about bows that no one but him could stretch or maces that no one could swing but him. According to Evliya, the sultan often dropped his clothes from one minute to the next and began wrestling with a guard just nearby. On other occasions, the sultan simply lifted Evliya over his head without any particular effort. Such a fit, and quite an agile sultan in relation to his stature, was well suited to warfare. And such a sultan was finally able to convince his subjects and soldiers that they could win the war with him!

After several unsuccessful attempts by his pashas in the first half of his reign to reclaim the lost territories, Murad decided to embark on a campaign in person. His first campaign took place in 1635, and the goal was to recapture Yerevan (Revan). They left Üsküdar in the spring and although they often stopped on the way to execute some bandits in Anatolia or to execute those against whom there were many complaints, they even reached Yerevan by July. Roughly a week after the siege, on August 8, Mirgune Tahmasp Quli Khan, the governor who ruled the castle, gave up the castle and surrendered. Murad appreciated that Mirgune Tahmasp Quli Khan accepted him as his new ruler and a deep friendship developed between them. The man's new name became Emirgün and he was with Murad until his death. According to some, it was Emirgün who pushed Murad to start drinking alcohol more and more often.

After the victory, Murad went to Tabriz with his troops, but they could not keep the city, and Murad also got sick, so they traveled to Van in the winter. And by the end of the year, they had returned to Istanbul, where Kösem Sultan was waiting for her son with a huge ceremony. The whole city celebrated Murad’s victory. Murad immediately ordered the construction of a pavilion inside Topkapi Palace in honor of the victory. It later became the Revan Pavilion. Murad planned every step wisely and always acted when the conditions were right. He did so when he dealt with the chief rebels of the 1632 uprising, and he did so when he wanted to get rid of his half-brothers, Bayezid and Suleiman, who posed a great threat to him. Murad knew that fratricide was not to the liking of the people, he knew that a sultan could easily be dethroned for this, but he definitely wanted to carry out his plans and bring back the inheritance from father to son. He, therefore, ordered the execution of the two princes at the moment when his popularity was at its highest and when the whole empire celebrated the victory of his. Although the execution of the two princes naturally shocked the people, everyone was preoccupied with the victory, the booming economy, so they did not turn against Murad.

Murad's popularity was not really diminished by the fact that the Safavids recaptured Yerevan in the spring of the following year. Of course, he had no idea to accept this either, but he waited again for the most opportune moment. It finally came in the spring of 1638. This time, he did not satisfied with Yerevan, he set a goal for Baghdad. By the end of October, he had already reached Baghdad and encamped around the city, and began the siege. On December 24, Bektash Khan, the governor of Baghdad, surrendered, so in January Murad was finally able to enter the coveted city, as did his great predecessor, Suleiman I, 100 years ago (in 1534). In Baghdad, Murad ordered that the mausoleum, previously built by Suleiman, be repaired and renovated.

Although Murad had a strong physique, his health was never good, and the horrific camp conditions worsened it. Especially since he mostly trained with his soldiers, he spent a lot of time with them to gain their support. His worsening alcoholism also did not help the situation. In Diyarbekir, the sultan eventually became so ill that they had to station there for months before they could reach Istanbul. While Murad was lying in bed, his Grand Vezir Tayyar Mehmed Pasha made an agreement with the Persian Shah to finally end the war that had lasted since 1603 and restored the Amasia Treaty of 1555, restoring peace between the two countries and allowing the Ottoman Empire to keep Baghdad.

Returning to Istanbul in June, the Sultan was greeted again with a huge celebration, glorified by all. True to his custom, he crowned this victory by building a new pavilion the Baghdad Pavilion. Unfortunately, he also tried to keep his other custom, so he ordered his brother, Prince Kasim (and perhaps Prince Ibrahim along with him) to the Revan Pavilion, where Prince Kasim was executed, and some said Ibrahim's life was saved only by the prayer and threat of their mother, Kösem Sultan. Others say Murad didn't want to execute Ibrahim just Kasim. Kasim's execution was particularly significant because, unlike the two princes who had been executed earlier, Kasim was a full-brother to Murad, and, according to contemporary accounts, they were even close to each other. By this time Murad was beginning to be overwhelmed by his illness, alcoholism, and paranoia.

His death and legacy

After Murad returned to Istanbul, he was in very poor health for months. He had several chronic diseases, but we don’t know much about them. Some said he may have had epilepsy, others said he may have had similar digestive problems as his father (Ahmed I) and grandmother (Handan Sultan). These were further aggravated by combat injuries, as Murad himself fought in his campaigns; and cirrhosis due to alcoholism.

Murad was able to recover from his fighting injuries, as in the early 1640s he celebrated Ramadan without any problems, met his vezirs, and took part in events. In fact, to further tire his already sick body, he regularly horse-rided to places, went hunting, and alcoholized with his friends. On one such occasion, Murad lost consciousness and was taken back to Topkapi Palace by his guards. The sultan sometimes regained consciousness, it seems that by this time he already knew he was dying. At his special request, he was transferred to the Revan Pavilion, where he had executed his younger brother a few months earlier. Maybe that's why he wanted to die there too. Not knowing who had been by his side in his last hours, but they probably couldn't have kept his mother away even if they had wanted to as they both were in the palace. According to some, on his deathbed, Murad also ordered the execution of Ibrahim, but there is no evidence of this.

A huge crowd gathered for Murad's funeral, his black horse was walking adorned in front of his coffin, and several of those present sobbed loudly. Thus, it is not true that the people rejoiced at the death of the Sultan. Although Murad was not perfect, he performed many cruel deeds, yet after decades he was the first sultan to conquer and he was the one who successfully restored the peace of the empire for which the people loved him. Murad IV was the last sultan to conquer in the true classical sense since no more sultans led a campaign in person. Murad resembled Yavuz Selim I or Suleiman I, who ruled in the early 1500s, rather than his immediate predecessors. Thus his person gave a strong end to the age of conquests and the heyday of the Ottoman Empire. He was buried in the mausoleum of his father, Ahmed I, because during his short life he did not have the opportunity to build his own mausoleum, and, according to many, he was not even preoccupied with architecture.

Used sources: C. Finkel - Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire; L. Peirce - The imperial harem; G. Börekçi - Factions and favourites at the courts of Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-17) and his immediate predecessors; S. Faroqhi - The Ottoman Empire and the World; C. Imber - The Ottoman Empire 1300-1650; F. Suraiya, K. Fleet - The Cambridge History of Turkey 1453-1603; G. Piterberg - An Ottoman Tragedy, History and Historiography at Play; F. Suraiya - The Cambridge History of Turkey, The Later Ottoman Empire, 1603–1839; Howard - A History of the Ottoman Empire; Öztuna - Devletler ve Hanedanlar; Uluçay - Padişahların Kadınları ve Kızları; : F. Davis - The Palace of Topkapi in Istanbul; Y. Öztuna - Genç Osman ve IV. Murad; G. Junne - The black eunuchs of the Ottoman Empire; R. Dankoff - An Ottoman Mentality: The World of Evliya Çelebi; R. Murphey - ‘The Functioning of the Ottoman Army under Murad IV (1623–1639/1032–1049):Key to Understanding of the Relationship Between Center and Periphery; S. Faroqhi - Another Mirror for Princes, The Public Image of the Ottoman Sultans and Its Reception

* * *

Születése és gyermekkora

Murad 1612 júliusában született I. Ahmed és kedvenc ágyasa, Mahpeyker Köszem második fia és ötödik gyermekeként. Ahmednek Köszem két fia mellett volt még egy fia, Oszmán herceg, a legidősebb gyermek. Murad ahhoz a herceggenerációhoz tartozott, akiknek először a történelemben nem kellett a testvérgyilkosság törvényétől tartaniuk. A II. Mehmed által törvénybe foglalt, de nála sokkal idősebb hagyomány szerint a trónralépő szultánnak minden testvérét ki kell végeztetni, a rend fenntartásának érdekében. Ahmed szultán azonban ennek nem tett eleget, mikor 1603-as trónralépése után életben hagyta öccsét, Musztafát. Így Ahmed fiai már egy új világba születtek. Tény azonban, hogy Ahmed sokáig nem volt biztos döntésében, így többször is megkísérelte Musztafa kivégzését, de végül a lelkiismerete és Köszem győzködése használt, így Musztafa megmenekült.

Murad koragyermekkorát relatív nyugalomban élhette, hiszen apja népszerű szultán volt, édesanyja a Haszeki szultána rangot viselte, igen befolyásos és népszerű asszony volt. Mindez azonban 1617-ben megváltozott. Ahmed szultán meghalt és egyfajta örökösödési káosz sújtotta a birodalmat. Az embereknek elege volt a testvérgyilkosságból, azonban Ahmed nem rendelekzett arról, hogy ki kövesse a trónon: öccse, Musztafa vagy legidősebb fia, Oszmán. Végül Musztafa trónralépésével hivatalosan is megváltozott az örökösödés, többé nem apáról fiúra szállt a trón, hanem a legidősebb férfi foglalta el azt. Murad és testvérei így életben maradhattak, azonban elzárva éltek a Topkapi Palotában, míg édesanyjuk Köszem a Régi Palotába költözött lányaival.

A következő évek meglehetősen zavarosak voltak, Musztafát mentális betegsége miatt hamarosan trónfosztották és Murad féltestvére, Oszmán került a trónra. Oszmán nagyon népszerűtlen, rossz uralkodó volt, aki bár uralkodásának korai szakaszában igyekezett korrekt viszonyt ápolni Köszem szultánával, később 1621 januárjában kivégeztette Murad édesbátyját, Mehmed herceget. Murad és öccsei minden bizonnyal rettegésben éltek innentől, anyjuktól, nővéreiktől távol, elzárva, kiszolgáltatva egy zsarnok uralkodónak, és az sem kizárt, hogy tanúi voltak a kivégzésnek. Végül Oszmán brutális meggyilkolása hozott enyhülést számukra. Ám ugyanakkor életreszóló leckét is adott Muradnak arról, hogy még egy szultán sem lehet biztonságban.

Trónralépés

Oszmán brutális kivégzése Halime szultánához és fiához, I. Musztafához volt köthető, így végül újra trónfosztották Musztafa szultánt, anyját pedig száműzték a Régi Palotába. Az öröklési sorban a mindössze 11 éves Murad következett. Korára való tekintettel a divan és ulema édesanyját, Köszem szultánát nevezte ki régensnek, míg Murad maga elég éretté nem válik az uralkodáshoz. Murad bár fellélegezhetett, hiszen ő lett a szultán, ilyen nehéz gyermekkorral bizonyára nem volt könnyű új életet kezdeni. Emellett fontos leszögezni, hogy Murad utoljára öt évesen 1617-ben tölthetett hosszabb időt édesanyjával, az 1617 és 1623 közötti hat évet anyjától elszakítva, bezárva élte, így feltehetőleg az is komoly nehézséget okozott kettejüknek, hogy újra kialakítsanak egy anya-fia kapcsolatot.

Murad nehezen kezelhető gyermek volt, Köszem több levele is fennmaradt, melyekben a nagyvezírnek panaszkodik arról, mennyire nem bír Muraddal és, hogy az mennyire nem hallgat rá, sőt olykor napokig találkozni sem hajlandó vele. Amellett, hogy az elszigeteltség éket vert közéjük, hasonló személyiségük sem segített sokat. Mind a ketten vezéregyéniségek voltak, igen erős akarattal, így nehezen jöttek ki egymással. Sokszor vitatkoztak egymással, mely viták után Köszem volt az, aki békülni szeretett volna Muraddal. Egyik nagy veszekedésük után például egy lovat ajándékozott fiának, máskor hatalmas ünnepséget rendezett neki. Emellett Köszem rendszeresen fejezte ki aggodalmát Murad egészségével kapcsolatban, ami arra enged következtetni, hogy talán Murad már ekkor egészségügyi problémákkal küzdött.

A birodalom Ahmed halálától kezdve fokozatosan süllyedt anarchiába. Több fontos területet is elveszítettek és hiába próbálták visszahódítani ezeket, nem jártak sikerrel. Továbbá a II. Oszmán kivégzése után fellázadó Abaza Mehmed Pasa dacára annak, hogy mindenkit felelősségre vontak a gyilkosságért, nem volt hajlandó elismerni Muradot új uralkodójaként és folytatta a lázadást. Ezt a lázadást sem sikerült leverni az ellene kiküldött pasáknak. A helyzetet fokozandó, 1625-ben pestis tört ki a fővárosban és több, mint százezer áldozattal járt. Murad először szintén ebben az évben lázadt anyja szava ellen. Köszem ekkor kötött egy megállapodást a spanyolokkal, Muradnak azonban nem tetszett az egyezség, ezért azonnal visszahívatta azt.

1628-ban aztán Murad is súlyos beteg lett, hetekig feküdt ágyban. Pontos betegsége nem derült ki, egyesek szerint ekkor kezdődött epilepsziája, mások szerint emésztőrendszeri problémái voltak. Öröm volt az ürömben, hogy legalább ebben az évben sikerült leverni Abaza Mehmed Pasa lázadását és elfogni a férfit. Ugyanebben az évben Murad újabb jelét adta annak, hogy hamarosan át kívánja venni az uralkodást és nyíltan szembe ment anyjával, amikor felbontotta nővére Fatma házasságát az admirális Çatalcalı Haşan Pasával, akit anyja kiemelt figyelemben részesített. Emellett Muradot egyre jobbn zavarta, hogy anyja szemethuny a korrupció felett. Köszem maga is nagy előnyökhöz juttatta az általa favorizált pasákat, ami sokakból váltott ki ellenérzéseket, különösen fiából, Muradból. Így került például fontos janicsár pozícióba Murad nővérének, Fatma szultánának az új férje, Hafiz Ahmed Pasa. Ez azonban a szpáhiknak és a Köszemet szerető janicsároknak is sok volt. Végül ez volt az az esemény, mely kijelölte Murad egyeduralmának kezdetét.

Az egyeduralkodó

1632-ben, Hafiz Ahmed Pasa kinevezése után szpáhi és janicsár lázadás tört ki, melynek során a lázadók kivégezték a nagyvezírt és Murad szultán több hűséges emberét, többet között közeli barátját, Musa Çelebit. Hogy a helyzet tovább bonyolódjon a katonák nyilvánosan követelték, hogy Murad mutassa meg nekik öccseit. Ezzel jelezni akarták neki, hogy ha akarnák le tudnák cserélni valamelyik öccsére; másrészt pedig keringtek olyan alaptalan pletykák, hogy Murad és Köszem megszabadultak a hercegektől. Murad kénytelen volt engedni a követeléseknek és bemutatta öccseit, akiket a katonák ekkor éltetni kezdtek. Murad ezt sosem felejtette el és sosem bocsátotta meg sem a lázadóknak, sem testvéreinek. Muradot tulajdonképpen ekkor mérhetetlenül megalázták, szövetségeseit, közeli barátját meggyilkolták. Ezt egy uralkodó sem hagyhatta. Murad azonban volt annyira megfontolt és intelligens, hogy nem azonnal kezdett bosszúhadjáratba, hanem csak akkor végeztette ki a hangadókat, mikor néhány hónap múlva hatalmát sikerült megszilárdítani.

Akárhogyan is, a lázadás után 1632 májusában Murad saját kezébe vette az irányítást és lemondatta édesanyját a régensi pozícióból. Köszem nem ellenkezett, félreállt, azonban igyekezett volna segíteni fiát, utat mutatni neki. Murad ezt nem értékelte és nem hallgatott édesanyja tanácsaira. Murad kényszeresen igyekezett anyját távol tartani a politikától és cselekedeteiből egyértelműen kiolvasható, hogy zavarta őt anyja nagy befolyása, az, hogy az elmúlt években sokkal nagyobb hatalma volt anyjának, mint neki. Épp ezért, amint a hatalmat saját irányítása alá vonta, Murad igyekezett anyja embereit - így például saját sógorát, a már említett Hafiz Ahmed Pasát - sorra leváltani, hogy édesanyja befolyása alól kivonva magát, elkezdhesse egyeduralmát.

Bár Köszem és Murad viszonyát kétségkívül megbélyegezte az 1632-es lázadás, hiba lenne azt gondolni, hogy Murad teljesen kizárta életéből édesanyját. Annak hárem vezetői tisztségét és édesanya mivoltát mindig tiszteletben tartotta, sőt egy 1632-ből származó beszámoló szerint kifejezetten fontos volt neki anyja véleménye a magánéletét illetően. Knolles ugyanis arról számolt ekkor be, hogy Murad hetekik lányának születése után feleségül akarta venni (vagy inkább Haszeki rangra emelni) a gyermek anyját, hogy kifejezze szeretetét a nő irányába, de mielőtt ezt megtette volna, kikérte Köszem véleményét. Érdekes kérdés, hogy ki volt ez a nő, ugyanis Murad korai uralkodásából egyetlen kiemelt státuszú ágyast ismerünk, Haszeki Ayşe szultánát, azonban nem tudjuk pontosan, kik voltak a gyermekei és mikor születtek.

Emellett mikor Murad hosszabb rövidebb időre elhagyta a fővárost, mindig anyját hagyta meg felügyelőnek, Köszem pedig mindig mindenről pontosan beszámolt fiának. Amikor Köszem problémát észlelt, azonnal jelezte azt a legrészletesebb leírással Murad számára. Előbbire egy konkrét példa történt 1634-ben, amikor Murad távollétében Köszem arról értesült, hogy egy müfti nem fogadta el Murad egyik döntését és felül akarta azt bírálni. Azonnal üzenetet küldött fiának "Én harcos oroszlán fiam, gyere azonnal! Pletykák terjednek a trónoddal kapcsolatban, az emberek pedig mozgolódnak." Muradnak nem kellett több, azonnal visszatért és minden vizsgálat nélkül kivégezte a müftit. Ez volt az első ilyen esemény a birodalom történetében, korábban sosem végeztek ki müftit. Egy másik alkalommal Murad Köszemet bízta meg, hogy diplomáciai megbeszéléseket folytasson a Krími Kánsággal.

A zsarnok

Murad személyisége nagyon megosztó. Sokan egyszerűen zsarnoknak tartják, azonban több volt ennél. Sokszor kegyetlen cselekedetei minden bizonnyal nehéz gyermekkorából származnak és a trónfosztástól való rettegéséből. Rengeteg legenda ismert, miszerint élvezettel gyilkolt embereket és sokszor ártatlanul kínozta őket, de olyanokat is hallani, hogy a szultán éjszaka kivont karddal rohangált az utcákon és megölt bárkit aki szembe jött vele. Ilyen formában ezek természetesen nagyon erős túlzások, ám tény, hogy sok olyan cselekedete volt, melyek nem tették különösebben népszerűvé. Köszem szultána igyekezett minden létező módon hatni fiára és saját jótékonykodásaival próbálta tompítani fia agresszív cselekedeteit.

Murad megtiltotta az alkohol és dohány fogyasztását, sőt minden kávézót bezáratott, mert szerinte a janicsárok és szpáhik itt gyülekeztek és szövetkeztek ellene. Aki pedig megszegte a szabályokat, súlyos büntetésre számíthatott, akár halálbüntetésre is. Hogy parancsait betartassa gyakran ment utcára álruhában és lépett fel a rendeletet megszegőkkel szemben személyesen. Ám az is tény, hogy ha ekkor igazságtalanságot vagy elkeserítő dolgot tapasztalt, az ellen is igyekezett tenni. Emellett sokat változtatott az alapvető törvényeken is, a büntetéseket megszigorította, gyakoribbá vált a halálbüntetés kisebb vétségek esetében is. A legendák megemlékeznek egy esetről, amikor egy vezírt végeztetett ki, amiért az megverte saját anyósát. Máskor pedig egy követet, Alvise Contarinit záratta börtönbe egy jelentéktelen bűnért. Contarini beszámolói ezen eset után megbízhatatlanná váltak, ugyanis gyakran írt hazugságokat, túlzásokat Muradról, személyes ellenérzései miatt. Ilyen volt például, mikor Contarini arról számolt be, hogy Murad ütlegeléssel fenyegeti rendszersen anyját, testvéreit és ágyasait. Azonban minden más bizonyíték épp az ellenkezőjéről számol be, így emögött a beszámoló mögött valószínűleg Contarini ellenszenve lehetett az egyetlen ok.

Bár kétségtelen, hogy Murad szigora túlzó volt, ennek köszönhetően sikerült rendbe szednie a birodalmat, a káosz és anarchia ténylegesen megoldódni látszott. Murad olyan kaotikus idők után ült a trónon, mikor a szultánokat kevésbé tisztelte a nép, mint régen. I. Szulejmán idejében a szultán szinte istenség volt, egy elérhetetlen, felsőbbrendű teremtmény. Egy szultánnak pedig, hogy uralhasson egy ekkora birodalmat fenn is kellett tartani ezt a látszatot. Az I. Ahmed halála után bekövetkező káoszban, mikor a nép Oszmán példáján meglátta, hogy a szultán igenis halandó, egyszerű ember, lerombolódott az évszázadok alatt felépített isteni kép. Murad ezt igyekezett újjáépíteni. Amikor ez szép szóval nem ment, akkor erőszakkal és szigorral tette, de rendet teremtett az országába.

Nem is meglepő ez tudva, hogy Murad példaképének I. Yavuz Szelimet tartotta, aki vasszigorral irányított, nem tűrte az ellentmondást. Murad - tanítója elméletét követve - úgy vélte, hogy a birodalom hanyatlása Szulejmán uralkodása alatt kezdődött, emiatt egyértelműen egy korábbi sikeres szultánt kellett imitálni. Emellett Muradnak nem titkolt célja volt a régi öröklési rend visszahozása is. Bár saját életét a törvény változásának köszönehtte, ő mégis úgy vélte, túl sok veszélyt tartogat magában, ha a szultánnak vele nagyjából egy idős vetélytársai vannak. Bár sokan egyértelműen elítélik ezért, be kell lássuk, volt igazság ebben. Oszmán brutális kivégzése, Musztafa bábként rángatása mind jól példázza, hogy a szultánok egyeduralma és kiemelt státusza megszűnt azzal, hogy hozzájuk hasonló vetélytársaik voltak és azzal, hogy elkezdtek érző lényeknek tűnni. Murad saját fiát akarta maga után a trónon látni, emiatt végeztette ki idővel öccseit, kivéve a mentálisan sérült Ibrahimot. Ez egyébként felvet több kérdést is, különös tekintettel Murad fiaira.

Murad gyermekeivel kapcsolatban elég sok a kérdőjel. Evliya Çelebi beszámolóiból tudjuk, hogy Muradnak rengeteg fia született, ám szinte kivétel nélkül mind elhunyt csecsemő korában, ugyanis meglehetősen rossz egészséggel jöttek világra. Sajnos legtöbb gyermeke esetében nem tudjuk, hogy mikor hunytak el. Annyi bizonyos, hogy 1634-ben egy követi beszámoló szerint két gyenge egészségű csecsemő fia volt. Azonban ezek ellenére is azt kell feltételezzük, hogy mikor Murad kivégeztette testvéreit (1635, 1638) legalább egy élő fia kellett, hogy legyen, aki nem csecsemő volt már. Legidősebb fia, Ahmed 1627-ben született és sokak szerint ő élt legtovább, igaz pontos dátum nem áll rendelekzésre halálát illetően. Vannak olyanok is, akik szerint Muradnak nem volt idősebb élő fia ekkoriban, egyszerűen csak a dinasztia végét akarta, ezért ölette meg testvéreit. Ezutóbbit alátámasztja a tény, hogy I. Ibrahim trónralépésekor Muradnak nem volt már élő fia, így talán Murad utolsó éveiben sem élt már egyikük sem. Azonban ez nem jelenti azt, hogy 1635-ben és 1638-ban sem volt már élő fia. Annyit tudunk 1637-ből egy követi beszámoló alapján, hogy Murad legalább 6 fia még egy éves kora előtt meghalt, a többiek egészsége pedig nagyon törékeny. Ám nem tudjuk, hogy a szerző mit és hány gyermeket értett a többiek alatt.

A magánember

Szultánként Muradot a legnagyobb jóindulattal is kénytelenek vagyunk valamilyen módon zsarnoknak tartani, hiszen rendeletei és sokszor a bűn mértékével nem egyensúlyban lévő büntetései erre utalnak. Ugyanakkor Evliya Çelebi leírásaiból igen sok minden tárul fel Muradról az emberről. Ezek alapján olyabá tűnik, hogy a kegyetlen Murad csupán egy álarc volt, ami mögé valódi természetét rejtette a szultán. Murad úgy vélte, hogy csak akkor tiszteli népe és katonái, ha félnek tőle. Minden cselekedete erre utal, így talán emiatt játszotta ezt a szerepet. Természetesen valódi személyiségétől sem állhatott nagyon távol ez, hiszen máskülönben nem tudta volna végrehajtani kegyetlenségeit.

Mit tudunk azonban mégis Muradról az emberről? Többek szerint rendkívül intelligens, művelt férfi volt, akinek igen jó volt a humora és tehetséges költő is volt. Evliya szerint "egy császár ő, lelkében egy dervis természetével." Utóbbi hasonlat különösen illő lehetett Muradhoz, mert nagyon tisztelte és elismerte a kerengő derviseket. Olyannyira, hogy egy Ömer nevű dervist az "apám" megszólítással tisztelt meg. Ömerrel egyébként gyakran szereztek zenét együtt. Murad a szöveget írta meg, a dervis pedig a dallamot adta hozzá. Azt pedig biztosan tudjuk, hogy a pletykákkal ellentétben, Murad nem volt őrült. Bizonyos szintű paranoia jellemezte ugyan, de ez figyelmebe véve a korábban vele történteket, azt, hogy első kézből tapasztalta bátyja halálát, majd féltestvére brutális meggyilkolását, nem különösebben meglepő. Azonban azon emberek között, akiket szeretett és akikben bízott Murad kivirágzott és megmutatta valódi arcát. Az igazi Murad egy ereje teljében lévő fiatal férfi volt, akivel a legszemélyesebb dolgokkal is lehetett humorizálni, akivel egyszerre lehetett mulatni és komoly dolgokról társalogni. Azt azonban Evliya sem vonta kétségbe, hogy Murad igen önfejű és hirtelen haragú ember volt, különösen anyjával szemben.

Szintén Evliyához köthető egy híres (vagy hírhedt) történet is, mely alapján sokan tartják napjainkban homoszexuálisnak a szultánt. Evliya történetének lényege, hogy egy gyönyörű személyről, Handanról beszélgettek a szultánnal, akit a szultán szeret és aki Evliya szerint is igazán elragadó. A történet szerint a szultán megkérte Handant, hogy a hajából vegyen ki egy rózsát és adja Evliyának, hogy ezzel felvidítsa a rosszkedvű Evliyát. A történetben alapvetően nem lenne semmi különös, ha mindez egy nyugati birodalomban történik. Ismerve a birodalom szokásait azonban egyértelművé válik számunkra, hogy Handan nem lehetett egy nő, hiszen egy háremhölgy nem tartózkodhatott idegen férfiak társaságában, különösen nem fedetlen hajjal. Emellett nehezíti Handan pontos felismerését, hogy a Handan egy uniszex név és hogy az oszmán nyelvben nincs férfi és női nem. Emiatt sokan gondolják, hogy Handan egy eunuch vagy egy fiatal férfi volt.Fontos tudnunk, hogy az Oszmán Birodalomban az 1800-as évek közepéig a homoszexualitás elfogadott volt, nem volt büntetendő. A legtöbb bordélyban (mert ezek is voltak a birodalomban) nem csak nők, de férfiak is elérhetőek voltak. Emellett II. Mehmed szultán óta a pederasztia elfogadott volt a szultánok és pasák között. Ezt az ókori görög hagyományt, mely egy felnőtt férfi és egy nála jóval fiatalabb férfi közti homoszexuális kapcsolatot jelenti, II. Mehmed (aki valósznűleg tényleg meleg vagy biszexuális volt) vette át, Konstantinápoly elfoglalása után. Később volt olyan szultán, mely élt ezzel a lehetőséggel és voltak akik nem. Azonban a pederasztia elsődlegesen inkább státuszszimbólum volt, mint szexuális vágy által hajtott kapcsolat.

Sokan pletykálták azt is, hogy Köszem szultána gyermekkora óta férfiakat küldött Murad ágyába, azonban semmi nem utal arra, hogy ez igaz lenne. Akárhogy is, Murad szexuális orientációja valószínűleg sosem fog kiderül és talán nem is számít. Életében két jelentős ágyas volt, Ayşe Haszeki, aki uralkodását szinte végig dominálta és aki Esmehan Kaya mellett bizonyára több gyermek édesanyja is volt; és egy másik nő, akinek nevét nem sikerült rekonstruálni és aki Murad utolsó éveiben került mellé és lett Haszeki. Ayşe volt azonban Murad kedvence minden bizonnyal uralma alatt végig, hiszen a nőt még revani hadjáratára is magával vitte. Ez a korai szultánok esetében előfordult, ám évszázadok óta nem éltek a hagyománnyal, hiszen megleehtősen kockázatos volt.

Zsarnokból az imádott szultán

Murad elődeihez hasonlóan tisztában volt azzal, hogy a leggyorsabb út a népszerűséghez egy sikeres hadjárat. Muradon különösen nagy volt a nyomás, ugyanis az ő uralkodása elején veszítettek el kifejezetten fontos területeket, így valahogy helyre kellett hoznia ezt. Murad igazán harcos természetű férfi volt, emellett fizikai teljesítményeiről is legendák szólnak. Igaz, hogy egészsége nem volt túl jó, de nagyon erős fizikummal bírt. Magas volt, robosztus alkatú, fekete hajú és szemű férfi, halvány bőrrel. Murad amellett tehát, hogy jóképű volt fizikai erejével is rendszeresen tudta lenyűgözni alattvalóit. Legendák keringenek íjakról, melyet rajta kívül senki sem tudott kifeszíteni vagy buzogányokról, melyeket senki nem tudott meglendíteni, csak ő. Evliya szerint a szultán gyakran egyik percről a másikra ledobta ruháit és birkózni kezdett egy éppen a közelben lévő őrrel. Más alkalmakkal a szultán egyszerűen felemelte Evliyát minden különösebb erőfeszítés nélkül a feje fölé. Egy ilyen fitt, és termetéhez képest meglehetősen mozgékony szultánhoz remekül illett a háborúskodás. És egy ilyen szultán végre el tudta hitetni alattvalóival és katonáival, hogy vele megnyerhetik a háborút!

Miután uralkodásának első felében több pasát is küldtek, hogy visszaszerezze az elvesztett területeket, ám minden kísérlet kudarccal végződött, Murad úgy döntött személyesen indul hadjáratra. Első hadjáratára 1635-ben került sor, a cél pedig Yerevan (Revan) visszahódítása volt. Tavasszal indultak Üsküdarból és bár útközben gyakran megálltak, hogy Anatoliában leszámoljanak kisebb bandákkal vagy kivégezzék azokat, akik ellen sok panasz volt, júliusra el is érték Yerevant. Nagyjából egy hét ostrom után, augusztus 8-án a kastélyt uraló helytartó, Mirgune Tahmasp Quli Khan feladta a várat és megadta magát. Murad értékelte, hogy Mirgune Tahmasp Quli Khan elfogadta őt új uralkodójának és mély barátság alakult ki köztük. A férfi új neve, Emirgün lett és a szultán kegyeltjeként haláláig mellette volt. Egyesek szerint Emirgün volt az, akinek hatására Murad egyre gyakrabban kezdett alkoholt fogyasztani.

A győzelem után Murad Tabrizbe ment a csapataival, azonban a várost nem tudták megtartani, ráadásul Murad is beteg lett, így telelni Van-ba utaztak. Év végére pedig visszaérkeztek Isztambulba, ahol Köszem szultána hatalmas ünnepséggel várta fiát. Az egész város Murad győzelmét ünnepelte és éltette a szultánt. Murad azonnal elrendelte egy pavilon építését a Topkapi Palotán belül a győzelem tiszteletére. Ez lett később a Revan Pavilon. Murad minden lépését okosan megtervezte és mindig akkor cselekedett, amikor a körülmények megfelelőek voltak. Így tett akkor is, mikor leszámolt az 1632-es lázadás hangadóival és így tett akkor is, amikor féltestvéreitől, a rá hatalmas veszélyt jelentő Bayezidtől és Szulejmántól kívánt megszabadulni. Murad tudta, hogy a testvérgyilkosság nincs a nép kedvére, tudta, hogy egy szultán könnyen belebukhat ebbe, azonban mindenképpen véghez akarta vinni terveit és vissza akarta hozni az apáról fiúra szálló trónöröklést. Ezért abban a pillanatban adta parancsba a két herceg kivégzését, amikor népszerűsége a legmagasabb volt és az egész birodalom győzelmét ünnepelte. Bár a két herceg kivégzése természetesen megdöbbentette az embereket, mindenki el volt foglalva a győzelemmel, a fellendült gazdasággal, így nem fordultak Murad ellen.

Murad népszerűségét az sem igazán csökkentette, hogy következő év tavaszán a szafavidák visszafoglalták Yerevánt. Természetesen esze ágában sem volt elfogadni ezt, de ismét kivárta a legalkalmasabb pillanatot. Ez végül 1638 tavaszán jött el. Ezúttal nem elégedett meg Yerevannal, Bagdadot tűzte ki céljául. Október végére el is érte Bagdadot és letáborozott a város köré és megkezdte az ostromot. December 24-én Bektash Khan, Bagdad kormányzója megadta magát, így januárban Murad beléphetett végre a hőn áhított városba, úgy mint nagynevű elődje, I. Szulejmán is tette 100 évvel ezelőtt (1534-ben). Bagdadban Murad elrendelte, hogy javíttassák meg és újítsák fel a korábban Szulejmán által építtetett mauzóleumot.

Murad bár erős fizikummal bírt, egészsége sosem volt jó, a rémes tábori körülmények pedig tovább rontottak állapotán. Különös tekintettel arra, hogy legtöbbször katonáival együtt edzett, sok időt töltött velük, hogy ezzel nyerje meg támogatásukat. Súlyosbodó alkoholizmusa szintén nem segítette a helyzetet. Diyarbekirben végül olyan rosszul lett a szultán, hogy hónapokig kellett ott állomásozniuk mielőtt Isztambulba érhettek volna. Amíg Murad a betegágyat nyomta, nagyvezíre Tayyar Mehmed Pasa egyezséget kötött a perzsa sahhal, hogy lezárják végre az 1603 óta tartó háborút, és visszaállították az 1555-ben kötött Amaszia egyezményt, így a két ország között helyreállt a béke, Bagdadot pedig az Oszmán Birodalom megtarthatta.

Júniusban, Isztambulba visszatérve újra hatalmas ünneplés fogadta a szultánt, mindenki dicsőítette. Szokásához híven ezen győzelmét is pavilon építéssel igyekezett megkoronázni, így megépíttette a Bagdad Pavilont. Sajnos más szokását is igyekezett megtartani, így édesöccsét, Kasim herceget (és talán vele együtt Ibrahim herceget is) a Revan Pavilonba kérette, ahol Kasim herceget kivégeztette, Ibrahim életét pedig egyesek szerint csak Köszem szultána könyörgése és fenyegetőzése mentette meg. Mások szerint Ibrahimot nem is akarta kivégeztetni Murad. Kasim kivégzése különösen jelentős volt, ugyanis a két korábban kivégzett herceggel ellentétben Kasim édestestvére volt Muradnak és korabeli beszámolók alapján még közel is álltak egymáshoz. Muradon ekkorra kezdett elhatalmasodni betegsége, alkoholizmusa és paranoiája.

Halála és hagyatéka

Murad Isztambulba való visszatérése után nagyon rossz egészségi állapotban volt, hónapokon keresztül nyomta az ágyat. Több alapbetegsége is volt, azonban ezekről nem tudunk sokat. Egyesek szerint epilepsziás lehetett, mások szerint neki is hasonló emésztőrendszeri problémái lehettek, mint apjának (I. Ahmed) és nagyanyjának (Handan szultána). Ezeket tovább súlyosbították a harci sérülések, hiszen Murad maga is harcolt a hadjáratain; valamint az alkoholizmusa miatt kialakuló májzsugor.

Murad harci sérüléseiből képes volt felépülni, ugyanis 1640 elején a Ramadánt minden gond nélkül ünnepelte, találkozott a vezíreivel, rendezvényeken vett részt. Sőt, hogy tovább fárassza beteg testét rendszeresen járt lovagolni és alkoholizálni barátaihoz. Egyik ilyen alkalommal Murad elvesztette az eszméletét és testőrei vitték vissza a Topkapi Palotába. A szultán néha magához tért, úgy tűnik ekkor már tudta, hogy haldoklik. Külön kérésére vitték át a Revan Pavilonba, ahol néhány hónappal korábban öccsét végeztette ki. Talán épp emiatt akart ő is ott meghalni. Nem tudni, hogy kik voltak mellette utolsó perceiben, de valószínűleg édesanyját ha akarták volna sem tudták volna távol tartani. Egyesek szerint halálos ágyán Murad kiadta a parancsot Ibrahim kivégzésére is, ám erre nincs bizonyíték.